Conservation Status

Taxus brevifolia

Nuttall 1849

Common names

Pacific or western yew, mountain mahogany (Peattie 1950).

Taxonomic notes

Syn: Taxus baccata Linnaeus subsp. brevifolia (Nuttall) Pilger; T. baccata var. brevifolia (Nuttall) Koehne; T. baccata var. canadensis Bentham; T. bourcieri Carrière; T. lindleyana A. Murray bis. The name T. baccata Hooker has been misapplied to this species (Hils 1993).

Description

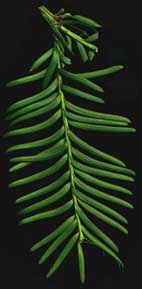

Dioecious shrubs or small trees to 15(-25) m tall and 50(-140) cm dbh. Bole straight to contorted, fluted; crown open-conical. Bark scaly, outer scales purplish to purplish brown, inner ones reddish to reddish purple, scales varying widely in size (2-50 mm wide). Branches ascendent to drooping. First-year shoots green, entirely covered by decurrent leaf bases; older twigs red-brown, resembling bark by the third year. Foliage buds inconspicuous, arising terminally or at the adaxial base of a leaf. Leaves green, linear, acute, mucronate, 8-35 mm long, 1-3 mm wide, pliable, often falcate, with a narrow median ridge on the upper surface and stomata in two yellow-green (not glaucous) bands of 5-8 lines on the lower surface, whorled but appearing 2-ranked, with a short (c. 1 mm) petiole and a 5-8 mm long decurrent leaf base; cuticular papillae are present along stomatal bands and epidermal cells as viewed in cross section of leaf are mostly taller than wide. Pollen cones solitary or clustered, adaxial on year-old shoots, buds globose, green, ca. 1.5 mm diameter. Seed ovoid, 2-4-angled, 5-6.5 mm, maturing late summer-fall, enclosed in a red aril ca. 10 mm diameter. Wood hard and heavy, about 640 kg/m3 (Hils 1993, Peattie 1950, and my pers. obs.). See García Esteban et al. (2004) for a detailed characterization of the wood anatomy.

Distribution and Ecology

USA: SE Alaska, Montana, Idaho, Oregon, Washington and California N of Sonora Pass; Canada: British Columbia, Alberta (in the Rockies, only below about 52° latitude). Found at 0-2200 m elevation in open to dense forests, along streams, moist flats, slopes, deep ravines, and coves (Hils 1993). See also Thompson et al. (1999). Hardy to Zone 6 (cold hardiness limit between -23.2°C and -17.8°C) (Bannister and Neuner 2001).

Distribution data for all species native to the Americas, from Conifers of the World, downloaded on 2018.01.26.

In most of its range, T. brevifolia grows as a tree beneath a closed forest canopy in late-successional forests dominated by large conifers such as Pseudotsuga menziesii and Tsuga heterophylla, but in drier open forests such as in the Siskiyous and the eastern Cascade Range it adopts a shrub habit similar to Juniperus communis, forming broad mats that may be several times wider than tall, and on such locations it may grow well up into the subalpine zone (pers. obs. 1986-2021). The seeds are wingless, so like all Taxus it is bird-dispersed, via defecation; dispersal has particularly been documented in some of the larger songbirds: Townsend's solitaire, varied thrush, and hermit thrush (Tirmenstein 1990). Based on postfire studies in western Oregon (Mitch Gillilan pers. comm. 2021.12.09), it has extremely low fire resistance. However, studies in western Montana indicate that tree ages often exceed the fire return interval, suggesting some level of resistance; alternatively, the old trees may represent residual unburned areas within a larger burned matrix (Tirmenstein 1990).

The species is commonly browsed by domestic ungulates (deer, elk, moose), especially in fall and winter when alternative forage sources are unavailable. They primarily browse foliage, but moose is reported to eat the bark as well, and moose can cause considerable damage to yew stands, which is reminiscent of the effects deer have had on Taxus canadensis (as well as on ornamental T. brevifolia) in eastern North America. It has been reported toxic to domestic livestock, but this appears unsubstantiated, likely based on reports that the European species (T. baccata) is toxic; cattle have been observed to forage on the foliage, with no apparent ill effects. The yew also provides excellent cover for native ungulates (Tirmenstein 1990).

Western yew is also allelopathic; Tirmenstein (1990) states "seedlings of other species are rarely found beneath yews. Pacific yew has exhibited inhibition both in laboratory experiments and in the field. Allelopathic compounds may be concentrated in senescent leaves and leached into the litter."

Remarkable Specimens

From 1959 to 2025, the largest was 148 cm dbh, 18.28 m tall, with a crown spread of 11 m. It grew in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest near Randle, Washington (Bob Pearson email 2018.07.18 reporting measurements taken that day). These measurements indicate a 2 cm DBH growth, a 2 m height growth, and a 2 m crown spread growth compared to earlier measurements dating from the late 1980's (Van Pelt 1996). I last visited the big tree in July 2018. At that time it was growing in a 50-year-old clearcut, on a moderately steep hillside near some other yews about 100 cm dbh. Evidently, at the time the stand was logged, they chose to leave the big yews when they removed the overstory Pseudotsuga menziesii and Tsuga heterophylla; the stand has since regenerated to nearly pure Tsuga. In 2018 the tree showed some loss of crown, but had survived the years of darkness growing in the understory of a pure Tsuga stand, and the stand was starting to open up and admit some light to the forest floor. In March 2025 the tree was reported dead, and to date, no new "big tree" has been named.

The tallest reported tree is 25.6 m for a tree at Capilano Lake, British Columbia, measured by Ralf Kelman; it is 74 cm DBH (Robert Van Pelt email 2019.02.13; measurement date unknown).

I have not found any real age data. Among Taxus in general, size and age seem to be correlated, and the largest trees of T. brevifolia are generally found in the understory of old forests dominated by Tsuga heterophylla and Pseudotsuga menziesii. Regeneration is rare, but seems to be most abundant in areas with adequate light, which suggests that it primarily occurs following severe disturbance. If the yews are about as old as the stand in which they grow, then ages of 350 to 650 years should be fairly common. Yew is rarely seen in older stands. Shrub-stature yew growing in open areas could live as long or longer, but age determination on such specimens is not feasible using tree rings, and I don't know of any studies attempting to derive ages in other ways.

Ethnobotany

Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast considered yew wood very valuable, using it for weapons and implements that require strength and toughness. Most coastal peoples used it for harpoons, fish spears, fish clubs, and dip net frames. Yew wedges were used to split cedar; in the Hesquiat, Saechelt, Suquamish and Nootka languages its name means wedge-plant. The Swinomish, Tlingit and Haida made yew war clubs. The Klallam, Kwakiutl, Makah, Nootka and Quinault used it for canoe paddles. The Makah preferred it for canoe bailers, halibut hooks, spoons and dishes, and square trinket boxes that are burnt out of one piece, and have lids. The Quinault used it for canoe bailers, spoons, needles, mauls, various tool handles, spring poles for deer traps, awls, dishes, bowls, pegs, drum frames and boxes. The Quinault, Swinomish, and Cowlitz use it for the digging stick used for roots and clams. Combs are carved of yew by the Cowlitz and Quinault. The Quinault, Slahelem and Tillamook made gambling-tokens from yew. Numerous ceremonial objects were carved from yew (Gunther 1945, Hartzell 1991).

Yew also had many medicinal uses, many of a magical nature, using the tree to impart strength. "Smooth sticks of yew are used by a Swinomish youth to rub himself to gain strength. The Swinomish use boughs to rub themselves when bathing. The Chehalis crush the leaves and soak them in water which is used to bathe a baby or an old person. It is supposed to make them perspire and improve their condition. While the Chehalis never drink this water, the Klallam prepare leaves in the same way, boil them, and drink the infusion for any internal injury or pain. The Cowlitz moisten leaves of yew, grind them up, and apply the pulp to wounds. The Quinault chew the leaves and spit them on wounds. This stings, but is supposed to be very healing. They are the only tribe making medicinal use of the bark, which is peeled, dried, and boiled. The liquid is drunk as lung medicine" (Gunther 1945). The Makah and Nootka also used the needles to brew an astringent bath. Yew was smoked, alone or with other plants, by the Klallam, Samish, Swinomish and Snohomish (Gunther 1945, Hartzell 1991).

Nearly everyone who could collect or trade for it, used it for bows (its Haida name means bow-plant). Among the interior tribes (some living beyond its range) that valued yew bows were the Lilooet, Shuswap, Flathead Salish, Nez Perce, Kalapuya, Umpqua, Yurok, Hupa, Karok, Shasta, Maidu, Wintu and Yahi. Many of these tribes also used yew medicinally (Hartzell 1991).

At present, yew has little commercial importance except as a source of taxol (see below), but remains popular among a host of minor industries because it is still relatively plentiful in comparison with most of the world's yews. Thus, it is used to make lutes and other stringed instruments; it fills much of the world's limited demand for yew bows; the Japanese import it for ceremonial toko poles; and it is used in naturopathic medicine. More traditionally, it has long been used by rural people in its native range for fenceposts, firewood, and tool handles (Hartzell 1991).

The bark is a natural source of paclitaxel (commercial name taxol), which has proven highly effective in treating various cancers (notably breast and ovarian cancer); exploitation of the species for medicinal purposes formerly threatened wild populations of T. brevifolia (Hils 1993), but a suitable drug substitute is now prepared from foliage gathered from cultivated plants of several Taxus species. See Taxus for further discussion.

Observations

Seen widely in Washington, where it typically occurs as an understory tree 3-5 m tall west of the Cascades, and as an understory shrub ca. 1 m tall and 2-5 across east of the Cascades. The best example of the type that I have seen west of the Cascades was in the headwaters of Silver Creek, latitude 46°38' N, longitude 121°50' W. This was in 1987 and the stand may have since been logged, as it was situated in a 400 year old stand of Pseudotsuga menziesii. Examples of the eastern Washington type are common in the western Wenatchee Mountains (north of Interstate 90).

Grows at the DeVoto Cedar Grove in northern Idaho (46.53920°N, 114.67538° W), a remarkable forest that seems to belong more in the western Cascades than in the Idaho Rockies. Overstory trees in the stand include Thuja plicata, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Picea engelmannii, Pinus ponderosa, Pinus monticola, and Abies grandis, with Taxus as an understory tree.

Grows mostly as an understory tree near Trinity Lake in northern California, e.g. at 40.82831° N, 122.89122° W.

Grows as a shrub in open subalpine country in upper Canyon Creek in California's Trinity Alps, e.g. with Picea breweriana at 40.97159° N, 123.02603° W.

Grows as a large understory tree (dbh commonly larger than 30 cm) in varied locations in western Washington, e.g. at Seward Park in Seattle (ca. 47.559° N, 122.252° W).

Remarks

The epithet mean "short-leaved", and Nuttall (1849) remarks on the species' overall similarity to Taxus baccata, excepting the shorter leaves.

Citations

American Forests 1996. The 1996-1997 National Register of Big Trees. Washington, DC: American Forests.

Nuttall, T. 1849. The North American Sylva, V. 3. Philadelphia: Smith & Wistar. P. 86 and plate 108. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/33189036, accessed 2019.03.01.

Tirmenstein, D. A. 1990. USDA Forest Service, Fire Effects Information System. Taxus brevifolia. https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/taxbre/all.html, accessed 2021.12.11.

Van Pelt, Robert. 1996. Champion Trees of Washington State. Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press.

See also

A 1993 Final Environmental Impact Statement prepared by the U.S. Forest Service contains several important appendices addressing the distribution of the species (Inventory), Insects and Diseases of Pacific Yew, Pacific Yew Plant Associations, Soils, Wildlife, and Cultural History of Pacific Yew.

Bighorn Botanicals, a commercial producer of yew extracts that provides a series of pages discussing the species' natural history, ethnobotany, conservation, and other topics (accessed 2019.03.01).

Burns and Honkala (1990).

Taylor and Taylor (1981).