Conservation Status

(species)

(var. megistocarpa)

Juniperus communis

Linnaeus 1753, p. 1040

Common names

Global: Common juniper; عرعر قزم [Arabic]; Գիհի ցածրաաճ [Armenian]; Ядловец звычайны [Belarusian]; Обикновена хвойна [Bulgarian]; ginebró [Catalan]; 欧刺柏 [Chinese]; Borovica [Croatian]; jalovec obecný [Czech]; Enebær [Danish]; Jeneverbes [Dutch]; harilik kadakas [Estonian]; Kataja [Finnish]; Genévrier commun [French]; Gemeiner Wacholder [German]; Közönséges boróka [Hungarian]; ginepro comune [Italian]; 주니퍼베리 [Korean]; Parastais kadiķis [Latvian]; Paprastasis kadagys [Lithuanian]; Эгэл арц [Mongolian]; einer [Norwegian]; Jałowiec Pospolity [Polish]; zimbro-comum [Portuguese]; Можжевельник обыкновенный [Russian]; borievka obyčajná [Slovak]; navadni brin [Slovenian]; enebro común [Spanish]; En [Swedish]; Ялівець звичайний [Ukrainian].

Var. depressa: prostrate juniper (Farjon 2010); gaagaagiwaandag [Ojibwe].

Var. nipponica: miama-nezu [Japanese] (Farjon 2010).

Var. saxatilis: mountain juniper; zwergwacholder [German]; ginepro nano [Italian]; genévrier nain [French]; xian bei ci bai [Chinese] (Farjon 2010).

Taxonomic notes

Many infraspecific taxa have been described in this highly polymorphic species, but most are sympatric, or merge into each other where they meet. Thus, the observed morphological differences are for the most part explainable on the basis of habitat differences, chiefly climate. This treatment follows the infraspecific classification of POWO for the most part, which in turn cites various publications by Adams as relevant authorities. The main difference is that POWO continues to regard var. saxatilis as present, pro parte, in North America; I agree with Adams (2014) in treating those observations as a mixture of var. depressa, var. kelleyi, and Juniperus jackii. The varieties are as follows:

- Juniperus communis L. var. charlottensis Adams (2008a). Type: Canada, British Columbia, Graham Island, 9 km S of Masset on Highway 16 in muskeg bog, 2007.07.08, R.P. Adams 10306 (holo BAYLU).

- Juniperus communis L. var. communis (Linnaeus 1753, p. 1040). Type: Europe, Alps, HSC s.n. (lecto BM).

- Juniperus communis L. var. depressa Pursh (1814). Type not designated.

- Juniperus communis L. var. hemisphaerica (J.Presl & C.Presl) Parlatore (1868). Type: Italy, Sicily, Mt. Etna, Todaro 458 (iso L, accessed 2023.02.16).

- Juniperus communis L. var. kelleyi Adams (2013). Type: USA, Idaho, Blaine County, shore of Little Redfish Lake, Adams 10892 (holo BAYLU, accessed 2023.02.16). "In British Columbia and Alaska, var. kelleyi and var. depressa appear to intergrade" (Adams 2013).

- Juniperus communis L. var. megistocarpa Fernald & H. St. John (St. John 1921). Type: Canada, Quebec, Madeleine Islands, Albright Island, Narrows, M.L. Fernald & B.H. Long 6729 (holo GH, accessed 2023.02.16).

- Juniperus communis L. var. nipponica (Maxim.) E.H.Wilson (1916). Type: Japan, Honshu, Prov. Nambu in alpibus, Tschonoski s.n. (iso BM, accessed 2023.02.16).

- Juniperus communis L. var. saxatilis Pall. (Pallas 1789). Type: lectotype, tab. LIV in Pallas (1789), designated by Farjon (2005). This is so often referred to by the epithets montana and nana that they may outnumber use of the name saxatilis.

Besides these, there are two nothovarieties, i.e. named hybrids of two varieties:

- Juniperus communis nothovar. intermedia (Schur) Nyman (1881) is the hybrid of J. communis var. communis and J. communis var. saxatilis (Enríquez-de-Salamanca 2024).

- Juniperus communis nothovar. intermedia (Schur) Nyman (1881) is the hybrid of J. communis var. communis and J. communis var. saxatilis (Enríquez-de-Salamanca 2024).

There is also a nothospecies, Juniperus × souliei Sennen (1917); this is the hybrid of J. communis and J. oxycedrus.

For many years botanists attempted to detail the infraspecific variation in J. communis on purely morphological grounds, and this led to a confusing mass of names. I don't even try to present all the synonyms, instead referring you to POWO. Finally molecular taxonomy was applied to the problem, and today most statements about infraspecific variation in J. communis can be based upon multiple studies, using multiple lines of molecular evidence.

Juniperus section Juniperus includes 13 taxa in three sister clades; the varieties of J. communis represent most of one of those clades, with related taxa in the clade including J. formosana, J. jackii, J. rigida, and J. taxifolia, species native to east Asia and western North America (Adams 2014). The monophyly of J. communis has been established using multiple lines of molecular evidence (Mao et al. 2010; Adams et al. 2011; Adams and Schwarzbach 2012, 2013). Studies of the infraspecific taxa have established a fundamental division between the eastern and western hemisphere varieties, as well as confirming the status of J. jackii as a distinct species closely related to J. formosana of Taiwan (Adams et al. 2011). Within the Eurasian groups, geography correlates with similarity, with var. hemisphaerica of western Europe most similar to var. saxatilis of Spain, var. communis of Europe grouped with var. saxatilis of central Asia, and var. nipponica of Japan grouped with var. saxatilis of Japan (Adams and Schwarzbach 2013, Adams et al. 2014). Similarly, the North American varieties charlottensis, depressa, kelleyi and megistocarpa are closely grouped (Adams and Schwarzbach 2012). Molecular clock estimates suggest a mid-Pliocene time for infraspecific radiation in J. communis, including initial migration into North America, and an earlier Pliocene time for divergence between J. communis and the other taxa in Section Juniperus (Mao et al. 2010). The strongest similarities between Asian and North American varieties are seen between plants of Kamchatka and the Queen Charlotte Islands, and the strongest similarities between European and North American varieties occur between plants of Greenland and northern Canada (Adams and Nguyen 2007), so it is not apparent what route J. communis took to enter North America.

Description

Decumbent shrubs to small trees, to 12 m tall and 50 cm dbh, usually multistemmed but occasionally monopodial; crown typically columnar to conical on trees. Bark gray-brown in thin strips, becoming fissured on large plants. Foliage usually dense and stiff but occasionally more open and lax, with numerous ultimate twigs. Leaves in alternating whorls of 3 (rarely 4), spreading to 30-90° from nodes 2-15 mm apart, stiff, slightly thickened at base, narrow-linear to broad-lanceolate, boat-shaped, 4-25 × 0.8-2.4 mm, straight or curved, abaxial face keeled or with a faint midrib, green, sometimes glaucous, with a single adaxial stomatal band bordered by green margins; apex obtuse to acuminate or pungent. Pollen cones axillary, solitary, 1-3 per leaf whorl, subglobose to ellipsoid, 3-5 mm long with 9-12 triangular microsporophylls. Seed cones axillary, nearly sessile, maturing in 18 months, at maturity globose, 4-13 mm diameter, with 1-2 whorls of 3 completely fused bract-scale complexes, sutures not visible, texture soft pulpy, purplish red to blackish brown, often with dark glaucous bloom. Seeds 1-3 per cone, triangular, oblong, 3-5 × 2-3 mm, light brown (Farjon 2010). See García Esteban et al. (2004) for a detailed characterization of the wood anatomy.

Farjon (2010) distinguishes J. communis from all other Juniperus by having seed cones smaller than 15 mm diameter and stomata in a single band, bordered by green, with no adaxial midrib. He does not provide a key to the varieties. Adams (2014, 2019) provides two keys, one to the varieties of Eurasia (extending west to include Greenland), one to those of North America:

Eurasian varieties (based on Adams 2014):

1a. Tree or upright shrub, leaves 15-20(-25) mm long. Var. communis.

1b. Prostrate or small shrub, leaves 8-15 mm long. 2.

2a. Stomatal band less than 0.25 to 0.5 times as wide as the green margin; restricted to Japan and Korea. Var. nipponica.

2b. Stomatal band equal to or wider than the green margin. 3.

3a. Bushy shrub to 2.5 m tall, leaves straight, 4-12 × 1.3-2 mm. Var. hemisphaerica.

3b. Low spreading shrub, leaves curved upwards, sometimes almost imbricate, 15 × 2 mm. Var. saxatilis.

North American varieties (based on Adams 2019):

1a. Strict (columnar) trees; leaves 15-20(-30) mm long, straight (not curved). Var. communis.

1b. Shrubs; leaves <15 mm long, curved. 2.

2a. Seed cones 10-13 mm diameter, much larger than leaf length; known only from southeastern Canada. Var. megistocarpa.

2b. Seed cones 6-9 mm diameter, smaller or slightly larger than leaf length. 3.

3a. Glaucous stomatal band at least 2 times as wide as green leaf margin, boat-shaped, curved leaves; mature seed cones longer than leaves; spreading, mat-like shrub; grows in bogs, Calvert Island to Queen Charlotte Islands, and north to Chichagof Island, Alaska. Var. charlottensis.

3b. Glaucous stomatal band 1.5 to 4 times as wide as green leaf margin, not in bogs, not in range of var. charlottensis. 4.

4a. Glaucous stomatal band 1 to 1.5 times as wide as green leaf margin; prostrate or low shrub with ascending branchlet tips (or occasionally a spreading shrub); leaves upturned, rarely spreading, linear to curved. Var. depressa.

4b. Glaucous stomatal band 2 to 4 times as wide as green leaf margin; spreading, mat-like or upright shrubs; leaves usually spreading, mostly linear. 5.

5a. Gland on brown leaf sheath long, narrow, raised; immature seed cones elongated to subglobose; leaves curved, boat-shaped, appressed to stem or proximal leaf; shrubs, usually prostrate or matlike on ultramafic rock (sometimes on lava, rarely on granite); northwestern California, western Oregon, Olympic Mountains of Washington. Juniperus jackii (included in this key as it is often confused with var. kelleyi).

5b. Gland on brown sheath elongated oval or if a long narrow gland, then with a rounded bottom end; immature seed cones globose; leaves most straight to slightly curved, not usually boat-shaped, free (not appressed to stem or leaf above on branchlet); usually shrubs to 0.5 m tall with upturned to elevated branchlets, not on serpentine, but grows in various habitats from granite, sandstone, alluvial, sand, and lava; northwestern United States, western Canada. Var. kelleyi

Distribution and Ecology

Afghanistan; Albania; Algeria; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Canada (all provinces); China; Croatia; Cyprus; Czechia; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Greenland; Hungary; Iceland; Iran; Iraq; Ireland; Italy; Japan; Kazakhstan; Kirgizstan; Korea; Latvia; Lebanon; Lithuania; Mongolia; Montenegro; Morocco; Nepal; Netherlands; North Macedonia; Norway; Pakistan; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Russia; Slovenia; Slovakia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Syria; Tazhikistan; Turkey; Turkmenistan; Ukraine; United Kingdom; United States; Uzbekistan; Yugoslavia. This is the most widespread conifer in the world, native to temperate Eurasia and North America N of Mexico, occupying an extraordinary range of habitats (Farjon 2005). As the varieties are in large part disjunct and have distinct ecological settings, see the variety descriptions for precise range and habitat discussions. See also Thompson et al. 1999. Hardy to Zone 3 (cold hardiness limit between -39.9°C and -34.4°C) (Bannister and Neuner 2001, variety not specified).

Infraspecific taxa of Juniperus communis; click on a color to see the variety, except that the lavender (pale purple) icons represent the "Saxatilis of North America" group, which includes various specimens assigned to var. saxatilis or one of its many synonyms. However, var. saxatilis does not occur in North America and these observations are generally assignable to either var. kelleyi (mostly in BC, WA and OR) or var. depressa (throughout the range of the species in North America). Some observations in northwest California, southwest Oregon and far western Washington will be assignable to Juniperus jackii. Map prepared using data from GBIF, downloaded 2023.02.15, DOI's include: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7yux6j, https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.dvcgy5, https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.tgsxf7, https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.2tcz33, https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.st5w6x, https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.j5jwbg, and https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.2py7hx. All collections represent geolocated preserved specimens with coordinate accuracy of at least 10,000 m, except varieties with <250 records also include iNaturalist observations. Only one sample per location is shown, usually the earliest collection record. See GBIF for further data on each observation.

Var. charlottensis

Native to USA: Alaska and Canada: British Columbia, where known from islands in Alaska S of Juneau, the Queen Charlotte islands group, and the neighboring mainland. Habitat is limited to sphagnum-dominated bogs (Adams 2008, 2014). The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. charlottensis, but since it has a fairly wide distribution within a habitat generally not subject to direct impact by humans, it would likely be assessed as "Least Concern".

Var. communis

Native to Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Czechia; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Iran; Ireland; Italy; Latvia; Lithuania; Montenegro; Netherlands; North Macedonia; Norway; Poland; Romania; Russia; Slovenia; Slovakia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Turkey; Ukraine; United Kingdom; Yugoslavia. Naturalized populations are also recorded in Canada and the United States. This variety is an extreme example of a habitat generalist, occurring from sea level to subalpine elevations, on a great range of substrates, and in a wide range of vegetation types excepting only the driest, wettest, darkest, and most frequently disturbed sites (Debreczy and Racz 2011).

The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. communis, but since it has an extremely wide distribution and often regenerates well in habitats impacted by humans, it would likely be assessed as "Least Concern".

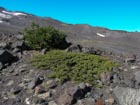

Var. depressa

Native to Canada (all provinces and territories) and USA: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Massachusetts, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Washington, Wisconsin and Wyoming. Occurs at 0-2800 m elevation on rocky soil, slopes, and summits (Adams 1993).

The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. depressa, but since it has an extremely wide distribution and occurs in many areas with little or no human impact, it would likely be assessed as "Least Concern".

Var. depressa almost disappeared during the Wisconsin glaciation; fossils of that age are only known from the southern Appalachian Mountains, and it expanded to its current range as the climate warmed and the ice melted (Adams 2008b).

Var. hemisphaerica

Native to Algeria; Andorra; Armenia; France; Georgia; Greece; Italy: Sicily; Morocco; Spain. The distribution is not well understood, and the great majority of collections have been made in Spain and Sicily. Habitat is rocky areas from sea level to 3000 m elevation (Adams 2014).

The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. hemisphaerica, but since it has a wide distribution and no mechanism for substantial human impact has yet been identified, it would likely be assessed as "Least Concern".

Var. kelleyi

Native to USA: Alaska, California, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington and Canada: British Columbia, Yukon. Few collections of this variety have been identified, and it seems likely than once reviewed, many extant collections of "var. saxicola" in the region will be reassigned to this taxon. Collections have been made at elevations of 760 to 1460 m, and habitat is described simply as "rocky areas" (Adams 2014).

The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. kelleyi, but since it has an extremely wide distribution and occurs in many areas with little or no human impact, it would likely be assessed as "Least Concern".

Var. megistocarpa

Native to Canada: Quebec (Madeleine Islands), Newfoundland and Labrador (Bay of Islands), and Nova Scotia (Sable Island); found on sand dunes, and on serpentines and dolomite barrens, at elevations of 0 to 500 m (Adams 2014). Typically occurs in sparsely vegetated sites or in areas of Empetrum heath in the ecotone bordering areas of conifer forest dominated by Abies balsamea or Picea rubens (Farjon 2010). This is the most morphologically distinctive variety of J. communis, with seed cones larger than its leaves.

The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. megistocarpa since 1998 and provides no rationale for the status assignment of "Endangered". Certainly the variety has an extremely small area of occurrence, but it is not apparent that it is subject to much in the way of human-caused threats, although it is likely that a stochastic event such as a superstorm might wipe out the occurrences on either Sable Island or the Madeleines.

Var. nipponica

Japan: Hokkaido and N Honshu, at elevations of 230-650 m (Farjon 2010). Adams (2014) would extend its range to southern Sakhalin and the S end of Kamchatka, and to Korea, although he identifies no specimens from these areas. The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. nipponica, and it is difficult to confidently assess that status without knowing the extent of the species. If it is found in areas like Sakhalin and Kamchatka, then the large area with little human impact would indicate a status of "Least Concern", but if endemic to Japan, then a threatened category may be warranted.

Var. saxatilis

Afghanistan; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; China; Czechia; Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Greenland; Iceland; India; Iran; Ireland; Italy; Japan; Kazahkstan; Korea; Kygyzstan; Mongolia; Montenegro; Nepal; Netherlands; Norway; Pakistan; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Russia; Slovenia; Slovakia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; Tajikistan; Turkey; Ukraine; United Kingdom. Presence in Canada and the United States is also widely asserted, but molecular analyses (op. cit.) have shown that those specimens are assignable to North American varieties. It is also likely that many far east Asian collections are assignable to var. nipponica and some Mediterranean collections to var. hemisphaerica. Really, the majority of collections have not been evaluated using modern criteria for distinguishing the different J. communis varieties; it is probably safe to say that for most of history any mat-forming juniper of the high mountains was assigned to var. saxatilis or one of its many synonyms, while any shrub or small tree in a lowland or mesic site was assigned to var. communis, with most collectors not even considering other possible varieties. Accordingly var. saxatilis can be described as a montane to alpine species (collections to elevations of >4000 m), usually on thin soils derived from silicate rocks (but occasionally from carbonates), in relatively xeric sites; also in Pinus mugo woodlands and as an understory plant in montane to subalpine conifer forests; also in riparian areas and wetlands (Farjon 2010).

The IUCN (accessed 2023.02.16) has not assessed the conservation status of var. saxatilis, but since it has an extremely wide distribution and occurs in many sparsely-populated areas, it would likely be assessed as "Least Concern".

Remarkable Specimens

Salomonson (1999) reported that the largest tree (which would be in var. communis) "is found at Råå in the province of Närke. It has a girth of 2.8 m. at breast-height." A 2016 measurement of a tree at Albero del Poeta, Italy, found a girth of 2.6 m (Monumental Trees 2017), and this is the largest recent record. The Monumental Trees database also reports trees of 1.2 to 1.5 m girth growing in Latvia, Poland, and the Netherlands, with measurements from 2013 to 2015.

The tallest specimen currently living is likely a tree of var. communis at Ryd, Skillingaryd, Sweden that was 17.20 m tall when measured in 2018 (Monumental Trees 2018; includes photos). The tallest one ever found grew at Lake Glypen in the province of Östergötland, but it fell in a storm late in 1980; the fallen tree was measured at 18.5 m long. Another tree, locally known as "Kungen" (the King), was 18 m tall, and grew at Röshult in Värnamo, Sweden. It was blown over in a 2005 storm (Jakobsson 2017).

The oldest trees are arctic. The oldest recorded specimen was a prostrate tree of var. communis in the tundra of northern Finland that was cut for sampling (thus is now dead), with the cross-section crossdated and measured on multiple radii. The limiting dates were found to be 845-2020, thus 1176 years plus the time prior to the earliest sampled ring, estimated at 10-200 years (Carrer et al. 2025). Shumilov et al. (2007) report a 676-year tree-ring chronology developed from living material of var. saxatilis (which they call Juniperus sibirica). The chronology was developed from a site at the polar timberline on the Kolya Peninsula (latitude 67.8°), making this one of the northernmost conifers, although exceeded by Larix gmelinii.

Ethnobotany

The human uses of Juniperus communis are distinguished more by geography than by variety. Broadly, they include medicine, food, uses of the wood, and use in horticulture.

Medical uses primarily concern traditional medicine. Examples from North America include use of decoctions and infusions based on roots, leaves, branches, bark, and cones; also, the branches and foliage were often burned to make a smoke or in a steambath. Ailments treated included stomach pain and other digestive ailments (e.g. heartburn, ulcers), cough and other lung ailments (e.g. asthma, tuberculosis), venereal disease, treatment of cold and fever, sedative, treatment of wounds, gynecological ailments, as an aid in childbirth, and in many other uses. Other uses, which could be seen as medical, included rubbing the branches against the body or burning the foliage to ensure good fortune in war, hunting, and initiation rites, or to counter the effects of evil spirits. These uses were found among tribal groups throughout the range of the species in North America: the Algonquin, Anticosti, Bella Coola, Blackfoot, Carrier, Cheyenne, Chippewa, Cree, Delaware, Inupiat, Gitksan, Hanaksiala, Iroquois, Kwakiutl, Malecite, Micmac, Okanogan-Colville, Shuswap, Tanana, Thompson, Navajo, Ojibwa, Paiute, Shoshone, and other peoples (Native American Ethnobotany Database 2023). Potential uses in modern medicine are plentiful; phytochemical studies have identified 310 chemicals in common juniper, 160 of which have known pharmacological activities (Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, accessed 2023.02.17).

Food uses, in contrast, were nearly nonexistent among native peoples of North America; they were limited to preparation of a tea from the branches, and even this likely had some medical purpose, for the plant was widely seen as a panacea (Native American Ethnobotany Database 2023). Conversely, the dried seed cones, usually called "juniper berries", have found plentiful use in modern cuisines of Europe. Although very bitter, they are used as a seasoning in various cooked dishes. They are also used to flavor gin, which derives its name from the French word for juniper: Genévrier; and to flavor other beverages such as the Finnish ale sahti, and also in traditional beers of Estonia, Latvia, Norway, and Sweden (multiple sources in the Wikipedia article Juniper Berry).

Since the plants almost never grow larger than small trees, their timber has not been widely used, but the wood and bark have found material uses. Among native Americans, the Ojibwa used the bark to build structures and mats, and the wood to make cradle boards. Historically the plants were harvested by the Ojibwa and sold as firewood and pulpwood. The Tolowa and Yurok used the dried seed cones to make necklaces and decorate dresses (Native American Ethnobotany Database 2023). The Scandinavians also use the wood to make small craft items, such as butter knives.

Horticulturally, Juniperus communis is among the most popular conifers, with cultivars of a fastigiate habit (usually derived from var. communis) or a decumbent habit (usually derived from var. saxatilis) especially popular (Farjon 2010). There are a great number of described cultivars; the Conifer Treasury (accessed 2023.02.17) provides photos of 89 of them, while the American Conifer Society (accessed 2023.02.17) describes 56 of them.

Observations

See the collection locales reported in the map above. There are also a large number of observations reported on iNaturalist, including all varieties, most of which are in publicly accessible locations.

Remarks

The species epithet means "common", and no conifer better deserves the name; but for Linnaeus, it was also very common in his homeland. As for the varietal epithets, charlottensis and nipponica refer to the Queen Charlotte Islands and Japan, respectively; both depressa and hemisphaerica refer to the low growth habit (spreading for depressa, condensed for hemisphaerica); kelleyi refers to Robert P. Adams' former student Walter Kelley; megistocarpa means "with a large fruit"; and saxatilis means "among the rocks".

Citations

Adams, Robert P. 1993. Juniperus. Flora of North America Editorial Committee (eds.): Flora of North America North of Mexico, Vol. 2. Oxford University Press.

Adams, Robert P. 2008a. Taxonomy of Juniperus communis in North America: Insight from variation in nrDNA SNPs. Phytologia 90(2):181–97.

Adams, Robert P. 2008b. Junipers of the World: The Genus Juniperus. Second edition. Trafford Publishing.

Adams, Robert P. 2013. Juniperus communis var. kelleyi, a new variety from North America. Phytologia 95:215–21.

Adams, Robert P. 2014. Junipers of the World: The Genus Juniperus (4th Ed.). Bloomington, IN: Trafford. 415 pp.

Adams, R. P. 2019. Juniperus of Canada and the United States: Taxonomy, key and distribution. Lundellia 21:1-24.

Adams, Robert P., and Sanko Nguyen. 2007. Post-Pleistocene geographic variation in Juniperus communis in North America. Phytologia 89: 43–57.

Adams, Robert P., Jin Murata, Hideki Takahashi, and Andrea E. Schwarzbach. 2011. Taxonomy and evolution of Juniperus communis: Insight from DNA sequencing and SNPs. Phytologia 93:185–97.

Adams, R. P., and A. E. Schwarzbach. 2012. Taxonomy of Juniperus section Juniperus: sequence analysis of nrDNA and five cpDNA regions. Phytologia 94:269–276.

Adams, R. P., and A. E. Schwarzbach. 2013. Phylogeny of Juniperus using nrDNA and four cpDNA regions. Phytologia 95:179–187.

Adams, Robert P., Alexander N. Tashev, and Andrea E. Schwarzbach. 2014. Variation in Juniperus communis trees and shrubs from Bulgaria: Analyses of nrDNA and cpDNA regions plus leaf essential oil. Phytologia 96(2):124–29.

Carrer, M., Dibona, R., Frigo, D., et al. 2025. Common juniper, the oldest nonclonal woody species across the tundra biome and the European continent. Ecology 106(1):e4514. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.4514.

Enríquez-de-Salamanca, Álvaro. 2024. Typification and distribution of two hybrids of Juniperus communis L. Phytologia 106(2):13–32.

Jakobsson, Fredrik. 2017.07.26. The tale of the tallest common juniper. http://ents-bbs.org/viewtopic.php?f=395&t=8067, accessed 2017.07.28.

Mao, K., G. Hao, J. Liu, R. P. Adams, and R. I. Milne. 2010. Diversification and biogeography of Juniperus (Cupressaceae): variable diversification rates and multiple intercontinental dispersals. New Phytologist 188:254–272.

Monumental Trees. 2017. Common juniper 'Albero del poeta' at Spiaggia di Pistis - Pistis beach in Arbus. https://www.monumentaltrees.com/en/ita/sardinia/carbonia/14586_spiaggiadipistispistisbeach/, accessed 2017.07.28.

Monumental Trees. 2018. Common juniper in Ryd in Skillingaryd, Jönköping, Sweden. https://www.monumentaltrees.com/en/swe/jonkoping/vaggeryd/19781_ryd/, accessed 2018.09.03.

Native American Ethnobotany Database. 2023. Results of search for "Juniperus communis". Available: http://naeb.brit.org/uses/search/?string=juniperus%20communis, accessed 2023.02.17.

Nyman, C. F. 1881. Conspectus Florae Europaeae p.676. Available: Biodiversity Heritage Library, accessed 2025.01.04.

Pallas, P. S. 1789. Flora Rossica 1(2):12; tab. LIV. Available: Real Jardin Botanico, accessed 2023.02.16.

Parlatore, Filippo. 1868. Flora Italiana, V. 4, p. 83. Available: Real Jardin Botanico, accessed 2023.02.16.

Pursh, F. 1814. Flora Americae Septentrionalis, vol. 2, p. 646. Available: Biodiversity Heritage Library, accessed 2023.02.16.

Salomonson, Ann. [no date]. Forest Sweden: The Swedish Forests. http://www.skogssverige.se/skog/skogen/eng/omtrad.cfm, accessed 1999.06.05, now defunct.

Sennen, 1917. Flora Catalunya p. 164.

Shumilov, O.I., E.A. Kasatkina, N.V. Lukina, I.Yu. Kirtsideli and A.G Kanatjev. 2007. Paleoclimatic potential of the northernmost juniper trees in Europe. Dendrochronologia 24(2-3): 123-130.

St. John, Harold. 1921. Sable Island, with a catalogue of its vascular plants. Proc. Bos. Soc. Nat. Hist. 36:58. Available: Biodiversity Heritage Library, accessed 2023.02.16.

See also

Adams, R. P. and R. N. Pandey. 2003. Analysis of Juniperus communis and its varieties based on DNA fingerprinting. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 31: 1271–1278.

Adams, R. P., R. N. Pandey, J. W. Leverenz, N. Dignard, K. Hoegh and T. Thorfinnsson. 2003. Pan-Arctic variation in Juniperus communis: History Biogeography based on DNA fingerprinting. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 31: 181–192.

Adams, Robert P., P. S. Beauchamp, Vasu Dev, and Radha M Bathala. 2010. The leaf essential oils of Juniperus communis L. varieties in North America and the NMR and MS data for isoabienol. Journal of Essential Oil Research 22(1):23–28.

Adams, Robert P., and Ram Naresh Pandey. 2003. Analysis of Juniperus communis and its varieties based on DNA fingerprinting. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 31 (11): 1271–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-1978(03)00036-X.

Adams, Robert P., Ram Naresh Pandey, J. W. Leverenz, N. Dignard, K. Hoegh, and T. Thorfinnsson. 2003. “Pan-Arctic Variation in Juniperus Communis: Historical Biogeography Based on DNA Fingerprinting.” Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 31(2):181–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-1978(02)00091-1.

Adams, Robert P., A. Gilman, M. Hickler, B. Sheets, and J. Vanderhorst. 2016. First molecular evidence that Juniperus communis var. communis from the eastern hemisphere is growing in the northeastern United States. Phytologia 98(1): 8–16. (megistocarpa-depressa hybrids)

Adams, Robert P. 2019. “Juniperus of Canada and the United States: Taxonomy, Key and Distribution.” Lundellia 21 (1): 1. https://doi.org/10.25224/1097-993X-21.1.

Elwes and Henry 1906-1913 at the Biodiversity Heritage Library. This series of volumes, privately printed, provides some of the most engaging descriptions of conifers ever published. Although they only treat species cultivated in the U.K. and Ireland, and the taxonomy is a bit dated, still these accounts are thorough, treating such topics as species description, range, varieties, exceptionally old or tall specimens, remarkable trees, and cultivation. Despite being over a century old, they are generally accurate, and are illustrated with some remarkable photographs and lithographs.

Farhat, Perla, Oriane Hidalgo, Thierry Robert, Sonja Siljak-Yakovlev, Ilia J. Leitch, Robert P. Adams, and Magda Bou Dagher-Kharrat. 2019. Polyploidy in the conifer genus Juniperus: An unexpectedly high rate. Frontiers in Plant Science 10 (May): 676. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00676.

Farjon (2005) provides a detailed account, with illustrations and details on the varieties.

Flora Celtica. [no date]. Uses of some common Scottish plants. http://www.rbge.org.uk/data/celtica/Plantuses.htm#Juniperus, accessed 2001.11.28, now defunct.