Hesperocyparis

Bartel & R.A.Price (2009)

Common names

New World cypresses.

Taxonomic notes

There are 17 species in Hesperocyparis. See Cupressus for discussion of the systematic relationships of this genus; briefly, it is sister to Callitropsis in a clade that also includes Xanthocyparis, and which is sister to a clade comprised of Cupressus and Juniperus. There is one synonym, Neocupressus de Laub., nom. superfl., which was described only days later than Hesperocyparis.

There has long been debate regarding the number of species in the genus. The large range of opinion occurs because cypresses generally occur in small isolated populations distinguished by small differences, interpreted by some as valid at species rank, but by others only at varietal or subspecific rank. Analyses performed in the 1990s using morphological and chemical data (e.g. Frankis 1992, Eckenwalder 1993, Farjon 2005) tended to "lump" taxa into a relatively small number of species. Conversely, the more narrow species concept was early advocated by Wolf (1948) in his monograph on the New World cypresses and was later supported, for the California species, by Lanner (1999). Using morphological, chemical and multiple lines of molecular/genetic data, Little (2006) also judged that many of the isolated populations are sufficiently distinct to be regarded as discrete species, and more recent molecular findings have consistently confirmed that finding, while also finding significant infraspecific variation in some taxa (see, e.g., Adams and Bartel 2009c).

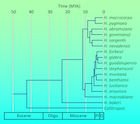

A significant, persistent taxonomic problem dogs the taxa here treated as H. arizonica, H. benthamii, H. forbesii, H. guadalupensis, H. lusitanica, H. montana, H. nevadensis and H. stephensonii: namely, that all of these taxa appear to represent a species complex rooted in northwest Mexico, an area which has not been adequately studied. This limits our ability to resolve phylogenetic relationships within Hesperocyparis. However, Terry et al. (2012) explored systematic relationships between the species of Hesperocyparis using nuclear and chloroplast DNA analysis. They considered all taxa except H. revealiana (sister to H. montana [Adams et al. 2014]), and included outgroup representatives from Callitropsis, Cupressus, Juniperus, and Xanthocyparis. They found H. bakeri solitary in a basal clade, and the remaining species in two clades: the California species H. abramsiana, H. goveniana, H. macnabiana, H. macrocarpa, H. nevadensis, H. pygmaea, and H. sargentii; and an Arizona-Mexico clade of H. arizonica, H. benthamii, H. forbesii, H. glabra, H. guadalupensis, H. lusitanica, H. montana, and H. stephensonii. Subdivisions within each clade were determined with lower confidence. In the California clade sister relationships exist between H. macrocarpa and H. pygmaea, H. goveniana and H. abramsiana, and H. nevadensis and H. sargentii. Various studies exist to provide more detail on infrageneric relationships (e.g. Adams and Bartel 2009a,b,c,d; Adams et al. 2010, 2012). The molecular data were further used in a biogeographic analysis by Terry et al. (2016) that proposed the New World cypresses (including Callitropsis) diverged from the Old World Cupressus and colonized from Asia at about the beginning of the Cenozoic, with migration from northwest to southeast as climates became increasingly cool and arid through Cenozoic time. The division between Callitropsis and Hesperocyparis occurred about 42 million years ago, with the major clades within Hesperocyparis arising from 23 to 12 million years ago (see top figure at right). The extant species are at most about 6 million years old. The Transverse Ranges of southern California represent a migration barrier separating the California and Arizona-Mexico clades.

Description

Monoecious evergreen shrubs or trees to 40 m tall, single- or multi-trunked. Bark gray, fibrous, exfoliating in fibrous strips; or gray to reddish-brown, leathery, exfoliating in small plates and curls. Twigs round to quadrangular, generally arrayed in space-filling clusters or, rarely, in flattened sprays. Juvenile leaves awl- to needle-like, opposite or in whorls of 3; adult leaves opposite, scale-like, appressed, overlapping, minutely denticulate

or rarely entire, often with a dorsal resin gland, leaves on vigorously growing shoots more elongate with an acute apex. Pollen cones terminal, sub-globose to cylindrical, 2.0-6.5 × 1.3-3.0 mm, yellow-green at maturity; microsporophylls decussate in 3-10 pairs, 3-6(10) sporangia in an irregular row per microsporophyll. Seed cones 10-50 mm long, more or less woody, subglobose to broad-cylindric, maturing in the second year, generally remaining closed at maturity and opening after many years or in response to fire, abscising after opening or after many additional years; scales opposite in (2-)3-6 pairs, thickened, peltate, abutting, shield- or wedge-shaped, boss generally >1 mm (especially prior to maturity), pointed, base level with or rising from edge. Seeds numerous, flattened, ovate to lenticular, irregularly faceted due to close packing, light tan to black, generally glaucous, generally warty with minute resin pustules in the seed coat; seed wings 2, membranous, narrow. Cotyledons 2-6, linear, slightly ridged with a blunt apex. Chromosome number, 2n = 22(-24) (Adams et al. 2009 and pers. obs. of plants in habitat).

Hesperocyparis differs from Callitropsis and Xanthocyparis in having 3-5 cotyledons (vs. 2), 3-6 pairs of peltate and heavily thickened seed cone scales (vs. 2-3 pairs, basifixed and not heavily thickened), and generally 60-150 seeds per cone (vs. <15). Hesperocyparis differs from Cupressus in having 3-5 cotyledons (vs. usually 2), and a generally glaucous seed coat (vs. not glaucous). Also, usually the ultimate 2 orders of branch segments are in 3-dimensional clusters, the ultimate branch segments not flattened in cross section, and the ultimate branch segment leaves monomorphic (vs. usually ultimate 2 orders of branch segments in 2-dimensional sprays, or ultimate branch segments flattened in cross section and ultimate branch segment leaves dimorphic) (Adams et al. 2009).

Distribution and Ecology

Cool north temperate regions to the northern subtropics in the USA, Mexico, and adjoining Central America. This table summarizes the species by their general areas of native distribution, listing them roughly from north to south:

| Species |

Distribution |

| H. bakeri |

USA: Oregon and California. |

H. macnabiana

H. sargentii

H. goveniana

H. macrocarpa

H. nevadensis |

USA: California. |

H. stephensonii

H. forbesii |

USA: California; Mexico: Baja California Norte. |

H. revealiana

H. montana

H. guadalupensis |

Mexico: Baja California Norte. |

| H. glabra |

USA: Arizona. |

| H. arizonica |

USA: Texas, New Mexico, SE Arizona; Mexico: Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, Tamaulipas, Zacatecas. |

| H. benthamii |

Mexico: Chiapas, Durango, Guanajuato, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Jalisco, México, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, Tlaxcala?, Veracruz, Yucatan? |

| H. lusitanica |

Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Mexico: Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Coahuila, Chihuahua, Colima?, Distrito Federal, Durango, Hidalgo, Jalisco, México, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit?, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, Quintana Roo, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Sonora?, Tamaulipas, Tlaxcala?, Veracruz, Yucatan?, and Zacatecas? |

Remarkable Specimens

The largest specimens represent H. macrocarpa, not in habitat; California includes a tree 576 cm dbh, and another 48 m tall. An ornamental specimen of H. forbesii was measured at 255 cm dbh and 21.3 m tall, and a specimen of H. pygmaea in habitat was measured at 213 cm dbh and 43 m tall. The other species are relatively small, rarely exceeding 100 cm dbh or 15 m tall. There are very few age data; an old record of 284 years for H. macrocarpa was probably based on a ring count from a stump.

Ethnobotany

Probably because of their very limited distribution, most taxa have little recorded use apart from occasional horticultural uses. One of the most widespread species, H. lusitanica, is commercially harvested as a timber tree in both Mexico and Guatemala and produces a fine, straight-grained lumber; it is also the most popular Christmas tree in Costa Rica. It was one of the first New World conifers to be brought to Europe, having been planted in Portugal since 1634 and in England since 1682. It has since become the most horticulturally important of the tropical cypresses, widely introduced in South America, Africa, Asia and elsewhere. Today it is grown in some parts of Africa as a forest tree. H. macrocarpa is another extremely popular ornamental in the western U.S., the U.K., New Zealand, and some other areas with suitable climate. It often attains impressive sizes, and does so quickly. In New Zealand, where it is called simply "macrocarpa", it is also harvested for fine carpentry such as cabinetmaking and musical instruments. The hybrid with Callitropsis nootkatensis, Leyland cypress, is a spectacularly popular horticultural item in much of the temperate zone, with scores of described cultivars.

Observations

See the species accounts. Many temperate zone arboreta contain good collections, too.

Remarks

The genus name means "western cypress".

Citations

Adams, R.P., J.A. Bartel and R.A. Price. 2009. A new genus, Hesperocyparis, for the cypresses of the western hemisphere. Phytologia 91(1):160-185.

Adams, Robert P., and Jim A. Bartel. 2009a. Geographic variation in Hesperocyparis (Cupressus) arizonica and H. glabra: RAPDs analysis.” Phytologia 91:244–250.

Adams, Robert P., and Jim A. Bartel. 2009b. Geographic variation in the leaf essential oils of Hesperocyparis (Cupressus) abramsiana, H. goveniana and H. macrocarpa: Systematic implications. Phytologia 91:226–243.

Adams, Robert P., and Jim A. Bartel. 2009c. Infraspecific variation in Hesperocyparis abramsiana: ISSRs and terpenoid data. Phytologia 91:287–299.

Adams, Robert P., and Jim A. Bartel. 2009d. Infraspecific variation in Hesperocyparis goveniana and H. pygmaea: ISSRs and terpenoid data. Phytologia 91:277–286.

Adams, Robert P., Jim A. Bartel, David Thornburg, and Andrew Allgood. 2010. Geographic variation in the leaf essential oils of Hesperocyparis arizonica and H. glabra. Phytologia 92:366–387.

Adams, Robert P., Frank Callahan, and Richard Kost. 2012. Analysis of putative hybrids of Hesperocyparis glabra x H. pygmaea by leaf essential oils. Phytologia 94:174-192.

Frankis, M.P. 1992. Cupressus. In: Griffiths et al. (eds) The New RHS Dictionary of Gardening 1: 781-783.

Terry, Randall G., Jim A. Bartel, and Robert P. Adams. 2012. Phylogenetic relationships among the New World cypresses (Hesperocyparis; Cupressaceae): Evidence from noncoding chloroplast DNA sequences. Plant Systematics and Evolution 298(10):1987–2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-012-0696-3.

Terry, Randall G., Matthew I. Pyne, Jim A. Bartel, and Robert P. Adams. 2016. A molecular biogeography of the New World cypresses (Callitropsis, Hesperocyparis; Cupressaceae). Plant Systematics and Evolution 302:921–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-016-1308-4.

See also

The Cupressus Conservation Project provides a wealth of information on New World cypresses, including a taxonomic review, historical accounts, cone photographs, and various other pertinent information.