Pinus culminicola

Andresen & Beaman 1961

Common names

Potosí piñon (Lanner 1981).

Taxonomic notes

Type: Mexico. Nuevo León: Cerro Potosí, near summit of mountain, Beaman 2675 (holo MSC; iso A, MONT, US). The plant had been collected much earlier on that mountain by C. H. Mueller in 1934 and 1935. A still older collection of the species (Ellareal & Carunza 4242), from the Sierra de Arteaga in Coahuila, had likewise been overlooked. Mueller referred his collections to P. flexilis, and Villareal and Carranza identified their material as P. cembroides (Andresen and Beaman 1961, Farjon and Styles 1997). I wonder, though, if Mueller's collection was actually P. stylesii, which was not described until 2008.

Malusa (1992) showed this piñon to be closely related to P. johannis and P. discolor, all of which share similar bark, habit, and leaf stomatal distribution (and thus a very distinctive appearance). See P. cembroides for a discussion of the systematics of the piñons, which presents much more recent molecular data confirming Malusa's finding and also showing a close relationship to P. remota.

Description

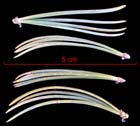

A shrub 1-5 m tall and up to 15-25 cm diameter, multistemmed or very low-branched, with a low, dense, rounded crown. Often forms extensive mats up to several meters thick and tens of meters across ("matorral"). The bark is thin, scaly, with peeling shaggy gray-brown plates exfoliating to expose fresh bright orange bark beneath (similar to P. johannis); bark on young stems smooth and gray. Branches numerous, the first-order branches often prostrate to assurgent, the higher-order branches assurgent to erect, short, thick, rigid but resilient, forming a dense, rounded to flat crown, usually matted with other individuals. Shoots short, thick, rough; the bases of the bract leaves (pulvini) decurrent, persistent, light brown turning gray. Bract leaves small, narrowly triangular to subulate, apex caudate, margins erose, persistent in part, light brown, weathering blackish gray. Vegetative buds broadly ovoid, the terminal bud 6-10 mm long, the laterals smaller, slightly resinous; the scales imbricate, free at apex, subulate-caudate, light brown. Fascicle sheaths initially 6-8 mm long, consisting of 4-6 imbricate, translucent, ciliate-margined scales; in mature fascicles the scales separate to form a rosette at the base of the fascicle, straw-coloured to gray, semi-persistent but mainly falling before the leaf fascicles. Foliar units in dense tufts on the ultimate branches. Leaves five in a fascicle (very rarely 4 or 6), 3-5 cm long, 0.9-1.3 mm thick, obtuse; stiff, curved toward the shoot apex, margins entire, stomata present on both adaxial surfaces, the abaxial surface dark green and the adaxial surface glaucous with 4-5 stomatal lines on each leaf face; retained 2-3 years. Leaf anatomy: Cross section triangular, with a convex abaxial side; hypodermis monomorphic, with 2 layers of cells; resin ducts 1-2, external, on the abaxial side; stele terete; outer cell walls of the endodermis not thickened; vascular bundle single. Pollen cones crowded on the proximal part (ca. 1/2) of a new shoot, ovoid-oblong when mature, 5-8 mm long, yellowish, turning yellowish brown. Seed cones are subterminal, solitary or paired, sessile or on a stout, short peduncle covered with subulate-caudate cataphylls. Immature cones subglobose, resinous, purple-brown, maturing in 2 years. Mature cones subglobose when closed, opening with a flattened base and remote, spreading fertile seed scales, then 3-4.5 × 3-5 cm; soon deciduous. Seed scales ca. 45-60, parting and spreading wide except the smaller, infertile proximal scales, irregular, often curved, thin, coarsely wrinkled, orange-brown, with 1-2 deep, cup-like depressions holding the seeds, bordered by membranous seed wing remnants, margins irregular, erose, yellowish on both sides, seed cups brown. Apophysis slightly raised, transversely keeled, rhomboid with a pointed apex, 10-15 mm broad, with a 4-5 mm wide blackish umbo, flat or slightly raised. Umbo dorsal, slightly raised, rhombic in outline, up to 5 mm wide, with or without a minute prickle, dark brown, often resinous. Fully developed cones in the upper crown have 10-15 fertile scales; small cones from low branches (with poor pollination and nutrient supply) are often lopsided with 1-10 fertile scales. Seeds dark orange-brown, 5-7 × 4-5 mm, with a rudimentary 0.5-1 mm wing that remains in the cone on seed release; the seed shell 0.5-1.0 mm thick, hard; endosperm white. Most seed is dispersed by mid-November, suggesting cone maturity in late October. Cotyledons 8-11 (Perry 1991, M.P. Frankis field notes 1991.11, Farjon and Styles 1997).

In the exposed sites where it is most common, it primarily assumes a krummholz form. This habit is very similar to other mountain dwarf pines, e.g., P. mugo in Europe and P. pumila in NE Asia, and is also assumed by normally erect pines such as P. albicaulis when they grow at alpine timberline sites. Adaptation to leaf cuticle abrasion by wind-blown ice is responsible for this habit.

Distribution and Ecology

Mexico: Coahuila and Nuevo León. It was first found in the summit area of Cerro Potosí in Nuevo León, 65 km W of Linares at 24.8729°N 100.2334°W. This is the most extensive known population. Three or four small populations are also recorded on the high ridges about 50 km northwest of there on the Nuevo León-Coahuila border; see Riskind and Patterson (1975) for details. Soils are rocky and calcareous. Existing climate parameters are not well-known due to a lack of weather stations at these summits. The species grows at 2965-3700 m, the highest mean elevaton of any pine (Perry 1991, M.P. Frankis field notes 1991.11, Farjon and Styles 1997, C.J. Earle field notes 2007.02.19). Hardy to Zone 7 (cold hardiness limit between -17.7°C and -12.2°C) (Bannister and Neuner 2001).

Pines of the Pinus cembroides complex. Green is P. culminicola. Purple diamonds are P. cembroides ssp. cembroides, purple stars are P. cembroides ssp. orizabensis, blue is P. discolor, brown is P. johannis, red is P. lagunae, and gold is P. remota. Based on GBIF.org downloads https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.pfuj4k (P. culminicola), https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.vvju45 (P. remota), and https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.5k7x9y (all other taxa), accessed 2023.03.09, with location uncertainty <10 km, and location duplicates removed.

The IUCN classifies this species as "Endangered" by human impacts due to a very limited distribution, with an area of occupancy of c. 10 km2, and a severely fragmented population that has seen recent substantial declines due to devastating fires, grazing, and trampling. The species is known only from a few mountain tops, and only on Cerro Potosí is it within a protected area; even there it is vulnerable to livestock grazing and human-caused fires. Observed regeneration rates are very low, particularly in times of drought. Also, since it has the highest mean elevation of any pine and is only found on the highest elevations of summits within its range, it may be vulnerable to the effects of climate change (Arévalo Sierra et al. 2017, Farjon 2013, Jiménez-Pérez et al. 2018).

On Cerro Potosí, I found the species at its lower elevational limits as an understory shrub with Agave and grasses in an open P. hartwegii-P. ayacahuite forest. (The stand may have also included P. stylesii, which had not yet been described at that time.) With increasing elevation and site exposure, the erect pines yield dominance to P. culminicola, and at the summit it forms extensive mats interspersed with occasional gnarled and stunted P. hartwegii. I also observed that the pine mats carry fire well; areas of up to several dozen hectares had burned on various sides of the mountain, the overall pattern consistent with an hypothesis of stand replacing fire at timescales of 50 to 200 years, although this would obviously be responsive to anthropogenic ignitions, which are quite possible at this easily accessible site.

Farjon and Styles (1997) report that at lower elevations, in the Sierra La Marta, Coahuila, P. culminicola grows in a scrub community with Quercus spp., Arctostaphylos, Ceanothus, Agave, and grasses; on the Cerro La Viega and the Sierra de Arteaga, Coahuila, they grow in a similar community that also includes Abies and Pseudotsuga (species not specified).

Pollen dispersal has been reported on Cerro Potosí to occur in late July, at 3690 m, which indicates a late fertilisation and short growing season (Farjon and Styles 1997).

In November 1991, after a hot dry two years in 1989-1990, the summit trees had a heavy cone crop of well-formed large (4 cm) cones, but lower trees had poorer crops of mostly somewhat smaller cones, presumably due to drought stress. In normal years, the reverse probably applies with conditions at the summit too cool for good crops (Frankis field notes 1991). The seeds are sought out and dispersed by gray-breasted jays and Clark's nutcrackers, which spread the seeds widely, hiding them in the ground for a winter food resource; as they hide more than they need, the surplus are left to germinate safe from marauding rodents (Lanner 1981).

Remarkable Specimens

The tallest specimens, up to 5 m tall, are at around 3400-3450 m elevation on Cerro Potosí; plants near the summit are shorter, mostly 1-1.5 m tall (M.P. Frankis field notes, 1991.11). All other species can attain larger sizes, so this can be described as the smallest of all pines.

The oldest known living specimens are 202 and 203 years, documented in the only two tree-ring chronologies yet developed for this species. The 202-year-old tree was on Cerro Potosí, collected by José Villanueva (doi.org/10.25921/7d3r-w379), and the 203-year-old tree was near Cerro San Rafael, also collected by José Villanueva (doi.org/10.25921/7v3x-qg40). Referring to these collections, Villanueva reports ages to 225 years (Villanueva et al. 2007).

During a field visit to Cerro Potosí in 2007.02, I observed evidence of traveling krummholz trees. This phenomenon, previously observed among Picea engelmannii in Colorado, occurs when a krummholz tree layers on its downwind side while succumbing to frost abrasion at its upwind side. Over time the entire tree travels downwind. The phenomenon obviously occurs slowly; radiocarbon dating has been used to ascertain travel rates of 0.9 to 2.6 centimeters per year for Picea engelmannii at Niwot Ridge, Colorado (Benedict 1984). The trees I saw on Cerro Potosí had left dead wood trails 1 to 2 m long, suggesting that they were at least a couple of hundred years old.

Ethnobotany

This may be the only piñon with no history of aboriginal use, as it grows at formerly uninhabited altitudes. Like the other piñons, it has edible seeds and no doubt the microwave station staff on Cerro Potosí now collect them for local use on occasion. It may also receive some use as firewood.

USDA hardiness zone 7. With its very attractive blue-green foliage, it is potentially a valuable slow-growing ornamental species for small gardens in cool dry areas, but it is still very rare in cultivation.

The tree-ring chronologies mentioned above were both used in a dendroclimatic reconstruction of soil moisture balance (Stahle et al. 2016).

Observations

It is very easy to see on the top of Cerro Potosí, being the dominant species from 3300 m up to a few metres short of the summit (3670-3713 m, depending on which map you use). There is a steep dirt road paved with large and angular rocks that zig-zags up the NE slopes right to the top, where it serves a microwave station. The road is passable in a 2WD vehicle with decent ground clearance and sturdy tires, and along it there are many fine campsites, but no reliable water. The road begins at the foot of the mountain in the village of Dieciocho del Marzo, and is prominently signed. Be prepared to sign in and pay an entrance fee (10 pesos in 2007) at the entrance station a couple of kilometers up this road. By the way, about a kilometer past the entrance station on this road is one of the easiest places to see the rare piñon P. nelsonii, which forms a small stand to the right (north) of the road. Other species visible on the drive up the mountain include Pseudotsuga menziesii subsp. glauca, Abies (not sure which species), P. stormiae, P. ayacahuite, and P. hartwegii. See Perry (1991) for directions to this road and advice on travel.

Remarks

The epithet culminicola means "growing on the summit."

Citations

Andresen, J. W. and J. H. Beaman. 1961. A new species of Pinus from Mexico. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 42: 437. Available: Biodiversity Heritage Library, accessed 2021.12.19.

Arévalo Sierra, José Ramón, Eduardo Estrada, Juan A. Encina, José A. Villareal, Job R. Escobedo, Yaretzi Morales, Israel Cantú, Humberto González Rodríguez, and José Isidro Uvalle Sauceda. 2017. Fire response of the endangered Pinus culminicola stands after 18 years in Cerro El Potosí, northeast Mexico. Forest systems 26(3):1-9.

Benedict, J.B. 1984. Rates of tree-island migration, Colorado Rocky Mountains, USA. Ecology 65:820-823

Farjon, A. 2013. Pinus culminicola. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2013: e.T32631A2822714. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T32631A2822714.en, accessed 2023.03.09.

Jiménez-Pérez, Javier, José Israel Yerena-Yamallel, Eduardo Alanís-Rodríguez, Oscar Aguirre-Calderón, and René Martínez-Barrón. 2018. Effect of cattle and wildlife exclusion areas on the survival and growth of Pinus culminicola Andresen & Beaman. Ecosistemas y recursos agropecuarios 5(13):157-163.

Malusa, J. 1992. Phylogeny and biogeography of the pinyon pines (Pinus subsect. Cembroides). Systematic Botany 17(1):42-66.

Riskind, D.H. and T.F. Patterson. 1975. Distributional and ecological notes on Pinus culminicola. Madroño 23: 159-161. Available: Biodiversity Heritage Library, accessed 2021.12.19.

Stahle, David W., Edward R. Cook, Dorian J. Burnette, Jose Villanueva, Julian Cerano, Jordan N. Burns, Daniel Griffin, Benjamin I. Cook, Rodolfo Acuna, Max C.A. Torbenson, Paul Sjezner, and Ian M. Howard. 2016. The Mexican Drought Atlas: Tree-ring reconstructions of the soil moisture balance during the late pre-Hispanic, colonial, and modern eras. Quaternary Science Reviews 149:34-60. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.06.018

Villanueva Díaz, José, Julián Cerano Paredes, D. W. Stahle, Vicenta Constante García, Lorenzo Vázquez Salem, and Juan Estrada. 2007. Árboles longevos de México / Ancient trees of Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 1:7–29.

See also

García-Aranda, M. A., J. Méndez-González, and J. Y. Hernán-dez-Arizmendi. 2018. Distribución potencial de Pinus cembroides, Pinus nelsonii y Pinus culminicola en el Noreste de México. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 5(13):3-13.

The species account at Threatened Conifers of the World.